BY KENNETH CRAYCRAFT

OSV News

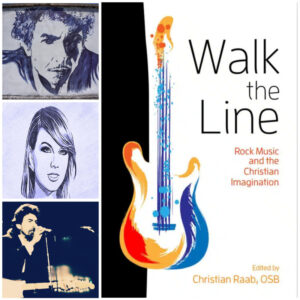

"Walk the Line: Rock Music and the Christian Imagination”

Father Christian Raab, OSB, ed.,

New City Press, 2023

251 pages, $24.95

Editor’s note: Benedictine Father Christian Raab of St. Meinrad Archabbey serves as Parochial Vicar of St. Joseph Parish in Jasper.

I write this seven years to the day after the announcement that the Swedish Academy had awarded Bob Dylan the Nobel Prize in Literature. Sara Danius, then permanent secretary of the academy, commended Dylan “for having created new poetic expressions within the great American song tradition.” Danius compared the perennial relevance of Dylan to such immortal poets as Homer and Sappho. Like these ancient Greeks, she noted, “Bob Dylan writes poetry for the ear ... poetic texts that were meant to be listened to, that were meant to be performed.” After hearing the announcement, novelist Salman Rushdie observed, “Dylan is the brilliant inheritor of the bardic tradition.”

It was precisely the bardic, aural qualities of ancient Greek poetry that caused Plato to put music at the center of his philosophy of the education of a good citizen. He said, “Rhythm and harmony permeate the inner part of the soul, affecting it most strongly and bringing it grace, so that if someone is properly educated in music and poetry, it makes him graceful. But if not, the opposite.” Thus, musical education cannot be separated from education in such virtues as “moderation, courage, frankness, high-mindedness,” as well as their opposite vices.

The common trope about rock music, of course, is that it contributes to those opposite vices. “The devil’s music,” rock is often associated with licentious sex and recreational drugs, not the classical virtues. Thus, rock-n-roll is often dismissed as having no redeeming qualities. In the wonderfully eclectic and consistently insightful new book, “Walk the Line: Rock Music and the Christian Imagination,” editor Benedictine Father Christian Raab and his nine co-contributors challenge that simplistic mindset.

To affirm the essential goodness of creation – and God as its author – means that wherever truth is expressed, it is a participation in the eternal mind of God, even if its expression is not expressly Christian. As “Lumen Gentium” puts it, “many elements of sanctification and of truth are found outside” the visible structure of the Church. Or, as Elizabeth Scalia notes in her foreword to “Walk the Line,” even unlikely forms of music may be “ways of prayer” that make a salutary contribution to the development of the human soul. This is true even when music reflects spiritual angst, loneliness or doubt, which are authentic experiences of religious growth and development.

Thus, Joseph Quinn Raab's chapter on George Harrison provides a Christian theological interpretation of Harrison’s search for the light of truth and salvation in non-Christian traditions. Rather than to obscure the substantive differences in those traditions, Raab uses Harrison’s music to highlight their distinctive notions of God and creation, while highlighting the human quest for enlightenment.

This is a useful contrast with Keith Lemma’s chapter on the music of U2. Bono and U2 are the most conspicuous Christian musicians discussed in “Walk the Line.” But Lemma does not allow their ambiguous connection to Christian faith go unchallenged. Instead, he points out the tension in the Christian religiosity of their posture and the public positions they have taken on important moral issues. Rather than denounce the band, however, Lemma challenges U2 to embrace a more consistent and authentic expression of Christian liberation.

Robert E. Alvis, on the other hand, makes a compelling case that Bob Dylan, the authenticity of whose famous late 1970s conversion to Christianity is perennially questioned, has returned to a deep, if not uncomplicated, Christian faith. Alvis especially highlights Dylan’s most recent album, “Rough and Rowdy Ways,” in making a compelling argument. I agree with Alvis that the album reflects “Dylan’s mature religious outlook,” expressing “values of inclusion, solidarity, and catholicity … while adhering to traditional Christian truth claims.”

Of course, a short review can only scratch the surface of this consistently outstanding book. Each of the contributors offer original, fresh Christian criticism of contemporary music. From such disparate subjects as Kurt Vile and Flannery O’Connor (in a chapter by William C. Hackett) to Taylor Swift and Benedict XVI (Brian Pedraza), the authors of these essays have made a valuable contribution to an appreciation of the relationship of Christian faith to rock-in-roll.

- - -

Kenneth Craycraft is an associate professor of moral theology at Mount St. Mary's Seminary and School of Theology in Cincinnati.