By Christina Capecchi

20-Something

The winter of 1915 was so cold in Northeastern Minnesota that a moose wandered into the small town of Biwabik and settled in a horse stable.

The winter of 1915 was so cold in Northeastern Minnesota that a moose wandered into the small town of Biwabik and settled in a horse stable.

The moose gradually won over the townspeople, who had initially tried to evict him. His memorable stay became part of Biwabik’s oral history, one day reaching the town’s basketball coach, an Iowa native named Phil Stong.

Phil had an ear for a good story. He worked like a reporter to gather all the details about the moose and then turned it into a chapter book, using the actual townspeople as its characters.

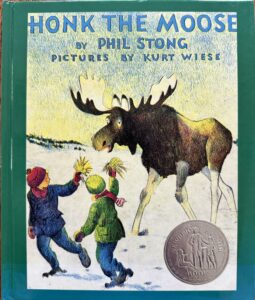

“Honk the Moose” was accepted by a New York publisher and illustrated by Kurt Wiese, the artist who drew pictures for the first English edition of “Bambi.” Published in 1935, “Honk the Moose” won a Newbery Honor Award the following year.

But time marched on, and eventually the book went out of print.

Steve Bradach decided to change that in 2000. A Biwabik native and a longtime city-council member, Steve knew “Honk the Moose” had potential to put his beloved town on the map. And the father of three believed new generations also deserved to be delighted by the tale.

“I wanted to give back to my hometown,” said Steve, now 59. “I wanted to make a difference.”

Hence began a pet project: The civil engineer dabbled in the foreign world of children’s publishing. The original publisher refused to talk to Steve, so he searched for Phil Stong’s family members.

Eventually, he tracked down the author’s nephew, who, it turned out, owned the rights to the book. He sold the rights to Steve and gave a blessing on the project.

There was only one problem: There were no digital files of the 1935 hardcover. It existed only in paper.

Steve fished for every copy of the book he could find in order to obtain the most pristine copy. Then he hired a company to scan all 80 pages — creating a digital file — and contracted a small publisher in Duluth, Minnesota, to print 6,000 copies.

To do so, he had to use the money that he and his wife, Kathy, had been saving to build a cabin on Lake Vermilion. The project cost about $30,000.

“I was a little nervous,” Steve said. “My wife asked: ‘Are we ever going to see the money again?’”

But the books sold quickly, and Steve commissioned a second run, this time of 5,000 copies. Nearly every copy sold, save for a few boxes he keeps in the back of his shop.

Biwabik experienced a surge of interest, including invaluable media coverage and enduring moose-themed traditions like “Honktoberfest” every fall. Steve made the money back, plus a $10,000 profit. He and Kathy completed their cabin, where they now live.

To Steve, now a grandpa of four, the lovable moose demonstrates the power of storytelling.

“Those stories you tell,” he said, “they stick. They create memories.”

As Christians, we are storytellers. We are called to share the Gospel, which means “good news.”

We have two narratives to tell: What Jesus did on Earth, and what Jesus continues to do in our lives. How He guides us and provides for us, showing up when we least expect it or most need it.

The work of recording the Bible was painstaking, undertaken by candlelight with handmade pens. Dip by dip, stroke by stroke.

Our duty is to honor and advance that work, to keep telling the story. That begins with reading Scripture. You cannot love something you do not know.

When you really believe in something, it becomes part of you. You see your life as a new chapter in the story started by the evangelist Mark in the year 70: a never-ending saga, a redemption tale, the greatest story of all time.

“In the beginning was the Word,” begins the Gospel of John, “and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.”

What happened next?

Christina Capecchi is a freelance writer from Inver Grove Heights, Minnesota.